Tonto National Monument

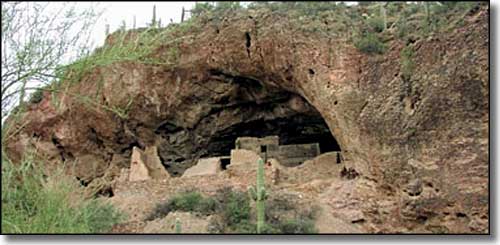

At Tonto National Monument there are two sets of masonry cliff dwellings that were occupied in the 13th, 14th and early 15th centuries (it was in the mid-15th century when the Tonto Basin was abandoned). The site is located between the Hohokam desert-dwellers to the south and the ancestral Puebloan groups in the mountainous regions to the east and north. Evidence of the merging of Hohokam and Puebloan pottery and architectural styles are found throughout the site.

European settlers probably knew of the cliff dwellings by about 1870 but it wasn't until Adolf Bandelier arrived in May of 1883 that there was official mention of the place. Bandelier worked his way through the upper and lower cliff dwellings, making notes and commenting on the almost perfect state of preservation he saw. In some areas he found sandals, thread and cotton cloth, all perishable materials that had been left where they fell some 400-450 years before, still in good condition.

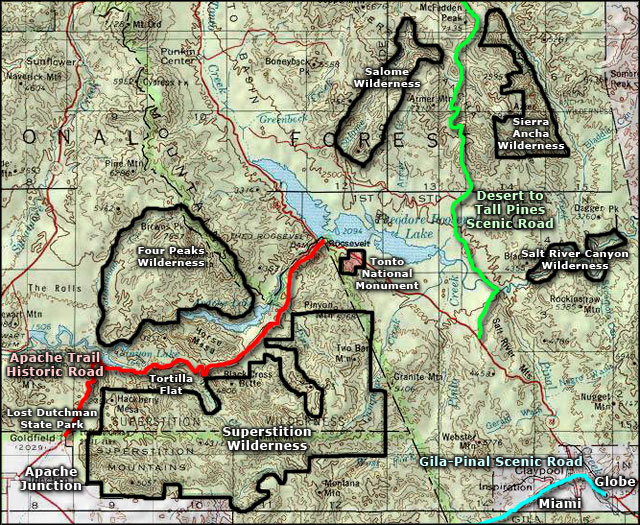

Within 20 years of Bandelier's visit, everything had changed radically. The railroad arrived in Phoenix in 1887 and every arriving train after that brought more settlers to the territory. Phoenix had been built on the side of the Salt River, an on-again-off-again stream that saw regular catastrophic flooding. The city was ravaged continually until the Bureau of Reclamation built the Theodore Roosevelt Dam at the confluence of Tonto Creek and the Salt River (about 4 miles from the Tonto cliff dwellings). Several years of construction brought thousands of workers, their families and sightseers into the area. Everyone wanted to visit the ruins and the ruins were being impacted heavily by all the careless traffic, never mind the digging and looting that went on after the crowds left for the day. Finally, on December 19, 1907, Teddy Roosevelt signed Proclamation 787, setting aside 480 acres around the cliff dwellings as Tonto National Monument. That proclamation also placed the property under the authority of the National Forest Service.

By 1911, when the Roosevelt Dam was finally finished, the Southern Pacific Railroad had built a hotel near the dam and was offering tours of the ruins. In 1929, working with the Forest Service, the Southern Pacific graded a road to the mouth of Cholla Canyon (where the picnic area is now). They dug a pit toilet there and then cut a 1-mile trail to the lower cliff dwellings. By 1932 the place had become so popular that the railroad extended the dirt road to where the parking lot is today and then built a stone caretaker's house there (that stone house served as a visitor center/museum until a new one was finally built in 1964). The next thing was to install chain link fences around the ruins and lock everything up at night. But a lot of damage was already done. The Tonto cliff dwellings suffered more damage and destruction in the 1920's and early 1930's than they had in the previous 600 years.

In July, 1933, Tonto National Monument was transferred from the Forest Service to the National Park Service and true preservation and protection finally arrived. By 1937 the National Monument included some 1,120 acres on which nearly 70 archaeological sites were eventually found. 1950 saw the arrival of funding for excavation and stabilization of the lower cliff dwellings.

The sad thing here is the story being enacted at Tonto National Monument was the same story happening all over the southwestern states at far too many archaeological sites. These days, discoveries and excavations are happening all the time, completely hidden from the public until the excavating and stabilizing work are complete. In some cases, the excavations are immediately reburied to protect them for the future.

Careless tourists are one big problem, looters are another. And so much of our history has been stolen and sold on the underground market...

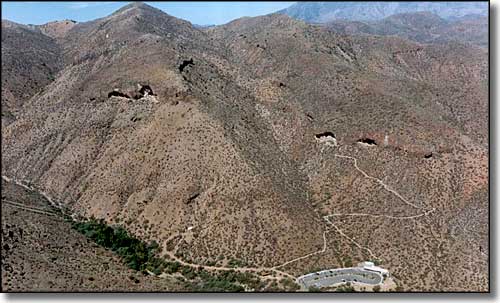

An overview of Tonto National Monument

Landsat 7 image

Tonto National Monument area map